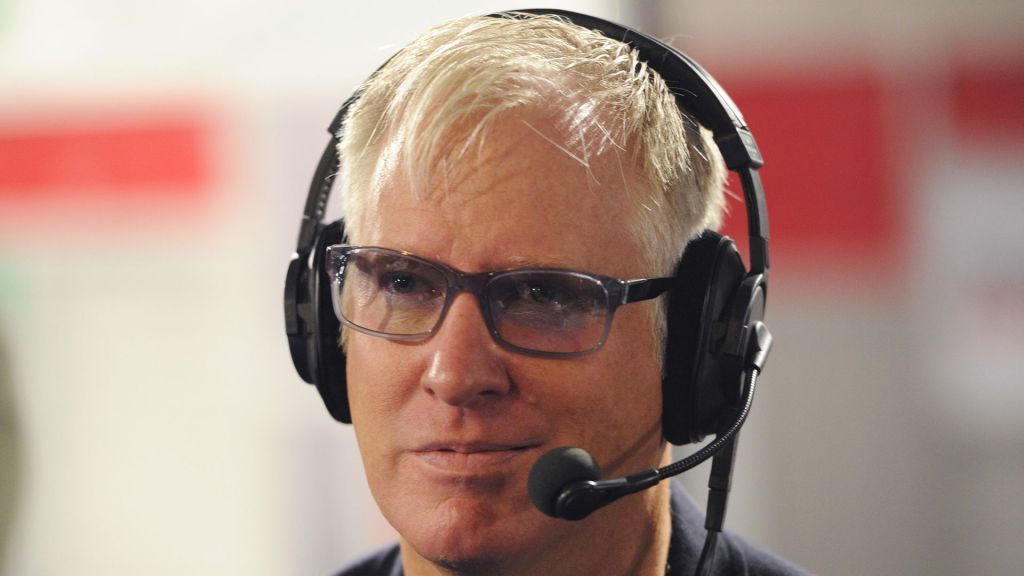

SIMONE DEL ROSARIO: For some, there’s nothing left to do but crack up over the price of eggs, if you’re not crying in the grocery aisle. Everyone’s in on the joke because everyone’s feeling the crunch of eggflation. The average price of a dozen eggs is now $4.25, well over double what it was one year ago. I’m joined now by Damian Mason, farm owner and host of the Business of Agriculture podcast, Damien, thanks for being with me today.

DAMIAN MASON: Thanks for having me, Simone.

SIMONE DEL ROSARIO: Look, the last time that we talked, we were talking about food inflation overall. But what’s happening with eggs goes far beyond that. What can you tell me about the magnitude of the bird flu as it stands in the U.S. today?

DAMIAN MASON: We started talking about avian influenza last year at about this time, if not sooner. So we’ve had this for a while. And a lot of people that are, you know, our suburban consumers are saying, ‘What’s this avian influenza?’ And by the way, I’m not a poultry epidemiologist, I’m not a poultry specialized veterinarian. I’m an agricultural economist. But I also read and I keep up with my clients that are in this space. You know, my understanding is…we’ve gotten rid of or depopulated about 44 million hens in the last so many months or a year. Our flock is about 325 million. So when you think about that, that’s about 13% of our herd or flock, if you will, that produced the eggs for us. So when you take away 13% of your hens, obviously, you take away 13% of egg production. So there’s our biggest problem is a simple issue of supply. But there’s some other things that play at that play also.

SIMONE DEL ROSARIO: And Damien, what are we seeing on the producer side of this? I mean, obviously, a lot of producers are losing a lot of hens here, what’s happening over there?

DAMIAN MASON: They’ve usually worked on really thin margins. So if there are death losses right now, there could be insurances in play. But the other thing that needs to be mentioned, and this is where I think the ag sector stands to get a little bit of a black eye. If you keep up with the business press this was last month in the Wall Street Journal, egg prices surged to records as bird flu reduces flocks. And then you go to read, ok it’s not just the bird flu, there’s the price of fuel, there’s the price of food feed for the chickens, there’s a price of labor…But there’s another thing at play. And you and I both saw this article. This was not too long after that article about egg prices soaring. This is about Cal-Maine, the nation’s largest egg producer, their Mississippi-based egg producer. And I want to tell you something that I think is really problematic for the sector, only because of a public relations situation. Their quarterly net income was $198.6 million at the end of November. That’s when their quarter ended. One year prior to that had been 1.17 million. I’ll give you those numbers again, because I know I’ve been a little number specific in our interview Simone, $198.6 million quarterly net income compared with $1.1 million the year prior, you’re talking about 190 times increase in net income. So at the farm level, the prices are so strong and they’re seeing the consumer is bending a little but certainly not breaking. So they’re passing along pretty significant price increases. I don’t believe that the grocery, the retailer, is making a great deal more money. They work on pretty thin margins. You know, the Kroger’s, the Walmarts, whatever of the world, but the farm gate is making an amazing amount of money if they have the birds and didn’t lose them to avian influenza. Their margins are numbers that they’ve not seen before, quite frankly.

SIMONE DEL ROSARIO: Yeah, the Cal-Maine stuff is pretty phenomenal. Again $198 million net income that is their profit, compared to 1.1 million for a quarter. It’s unbelievable. Their stock price is up 30% over the last 12 months. I looked up some of their specifics, their feed costs, as you mentioned, food was getting more expensive. Their feed costs increased 30% from the quarter to the one a year ago, but they’re selling at double the price. And on top of that, Cal-Maine say they don’t have a single positive test of avian flu at any of their facilities either owned or contracted. How are they getting away with this amount of record revenue, record profits.

DAMIAN MASON: And you know, I’m an ag guy. So I want to make sure that I’m putting out here there’s a lot of times when everybody in ag has worked on margins that were so paltry, you would scoff at them, you know. And so I want to point that out….There are those who would say, ‘Who the heck would ever put this much money and effort and risk in something with a 4% to 6% single digit return on your capital?’ That being said, I believe it’s gotten almost on the verge of excessive because they know the consumer still is really pushing eggs, eggs tend to be pretty inelastic in demand. It’s not like, you know, perfume or something that you don’t really need. Eggs are pretty much, you know, a staple…The producers seem to be capitalizing on that and padding the margins, obviously, by about 190 times what they were just a year ago. My concern for the ag sector is that when the consumer goes and Mrs. housewife, I’m sorry, Mrs. Consumer, if you will, buys these eggs over here at Kroger, this was $5.49 just yesterday evening, they were about $1.50 here in Phoenix, Arizona, about $1.50 for a grade A large eggs at Kroger a year and a half ago. So we’re talking about three and a half times, roughly three and a half times what the price is, when the consumer sees that after a while they start to feel a little bit jaded, a little bit, like you know, I’m being taken advantage of. And then they start calling for action. Think about, say fossil fuels, the consumer goes and pumps up and says, Wait a minute, how did gas go to $4.69 when it was just $3 six months ago, and then they are clamoring and then politicians want to get a little bit of play out of it. So then politicians say, ‘we’re gonna conduct investigations and we’re gonna threaten a windfall profit, profit tax.’ I almost wonder if we’re going to see in the next couple of weeks, we got new Congress, we got you know, the media buzz storm, Simone, are we going to start hearing politicians calling upon large egg, big egg, if you will, to come in before Congress and talk about how you’re passing along these and extorting the consumer? Will anything come of it? No, probably not. I mean, did all of a sudden Exxon or Shell Oil forfeit all their money over windfall profits? No, but it’s a bad look. And that’s my concern, frankly.

SIMONE DEL ROSARIO: Yeah. And when we are talking about Cal-Maine, we are talking about big egg here, like you had said, largest producer and distributor in the United States. And to your point, though, I looked back maybe five quarters and had found operating loss. So as you had said, you know, they’ve got lots of profits right now, but some quarters, they are operating at a loss. That said, after reporting record sales, Cal-<aine’s stock price actually dropped the last time they reported these quarterly earnings. Is that a sign that change is coming?

DAMIAN MASON: Production will catch up. And I imagine that the shareholders are saying, Yeah, we’re going to ride out these huge profits right now. But what does, what do we always say, the cure for high prices, Simone, is high prices, high prices are going to create more hens which are going to create more eggs. And then we’re going to end up with a bunch of eggs. And when there’s a bunch of eggs and then the supply chain a little bit more normalized, we can’t change the labor issue. We may be done with 99 cent per dozen eggs, but we’re going to definitely come down from where they are, it’s a matter of getting production ramped up. Unless you believe that avian influenza is something that we never get a handle on, but we had this in 2015, within about six months, we were through it. This one has lasted a little longer. This avian influenza and again, I’m not a poultry epidemiologist, but I can tell you that this avian influenza globally is stuck around longer than past bouts of it.

SIMONE DEL ROSARIO: Damian Mason, host of the Business of Agriculture podcast, thank you so much. Always appreciate your insights on this.